Author Archives: Admin

Zhen Yi Tang: “We Are Just Custodians of an Era”

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Zhen Yi Tang: Focusing on Factory Porcelain for Twenty Years, “We Are Just Custodians of an Era”

Upon entering Jingdezhen, the smokeless chimneys and abandoned porcelain factories silently narrate a bygone era of collective effort in the state-owned porcelain industry. Collaborations among modern ceramic masters, extremely detailed process management, and the revival and innovation of ancient techniques created a peak in ceramic art. This era produced later masters, artisans, and artists…

With the tides of history, today’s Jingdezhen is filled with countless independent studios and art spaces.

That unforgettable era of brilliance, those artistic masterpieces created by the entire city’s efforts, are surprisingly well-preserved in a place called “Zhen Yi Tang.”

“We are custodians of an era,” said Jiang Jingchen, the founder of Zhen Yi Tang. She believes that factory porcelain will be rediscovered by more people in the future.

Jiang Jingchen describes herself as someone who doesn’t cling to home.

This seems entirely plausible. She has kept her hair short for nearly a decade, wears simple clothes, and goes makeup-free. She’s been accustomed to living away from home since childhood and even ran a clothing business.

Her past experiences have deeply influenced her values. Even now, as she focuses on promoting factory porcelain in Jingdezhen, she adheres to certain principles: respect for every penny earned through hard work, emphasis on contracts, and helping friends whenever possible.

01 An Accidental Act That Preserved a Treasure Trove of “Factory Porcelain”

Factory porcelain entered Jiang Jingchen and her father’s lives by chance.

Before returning to Jingdezhen, 21-year-old Jiang Jingchen was in the clothing business. Operating three stores in a prime urban location was proof enough of her independence and pride.

From her father, she learned about this unexpected chapter of their lives.

The 1990s were a time of upheaval for Jingdezhen. After the founding of New China, the ceramic industry underwent mergers and reorganizations, leading to the establishment of the “Ten Great Porcelain Factories,” which leveraged state-owned enterprise advantages to innovate techniques and technologies. As state-owned factories gradually shut down or restructured, a vast quantity of fine porcelain was left behind—this is what people now call “old factory porcelain.”

Out of a love for these treasures and a sense of Jingdezhen nostalgia, the Jiang family took in this batch of factory porcelain.

“In the 1990s, we collected over ten million yuan worth of porcelain,” Jiang Jingchen recalled.

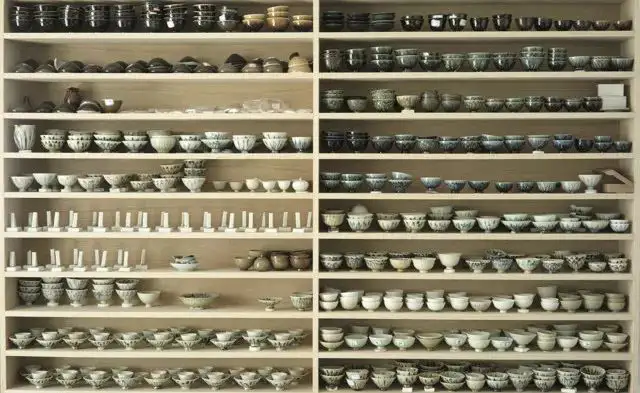

At the time, factory porcelain wasn’t yet popular. Countless vases, porcelain paintings, sculptures, and tea ware lay quietly on the concrete floors of dimly lit warehouses. As the planned economy transitioned to a market economy, the Ten Great Factories declined, the porcelain industry collapsed, workers were laid off, and Jingdezhen entered an era of competitive workshops.

Years later, when Jiang Jingchen’s father reopened the long-sealed warehouse door with friends, everyone’s eyes lit up at the sight of the dust-covered porcelain. This was a treasure trove.

02 A Rising Star in the Ceramic World

In the ceramic collection world, “factory porcelain” refers to ceramics produced by Jingdezhen’s factories from the 1950s to the 1990s during China’s planned economy era. The “factory porcelain” of that time has now become history.

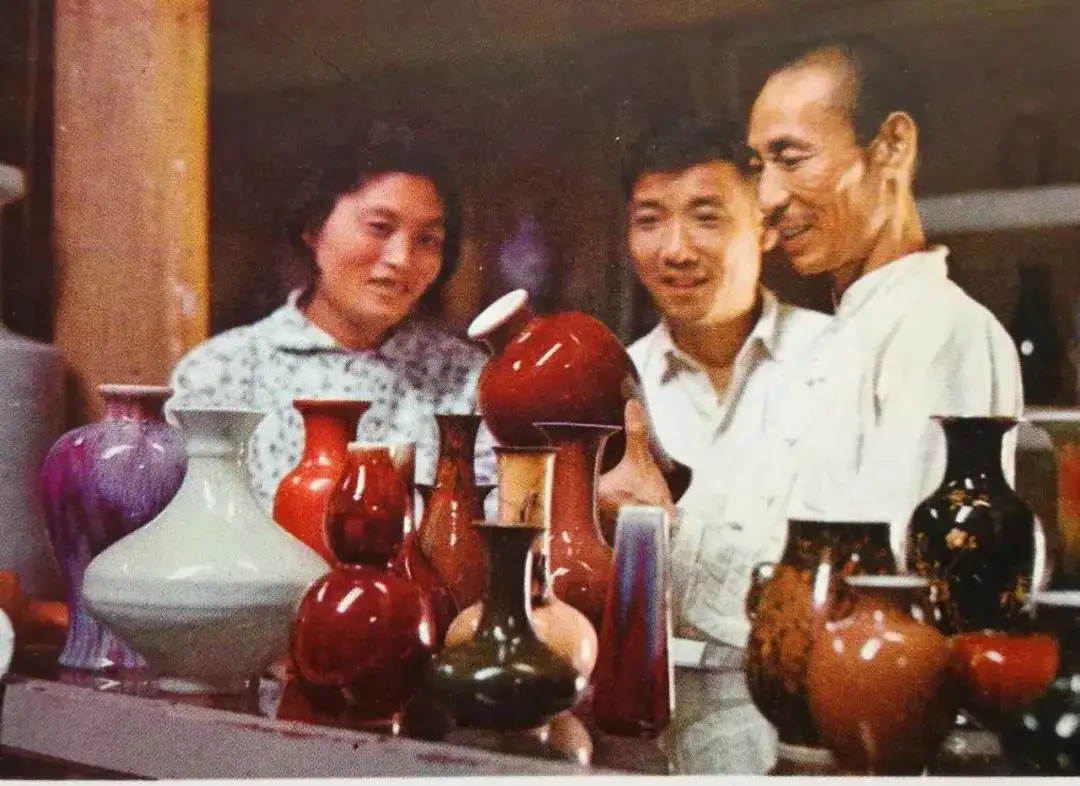

Undoubtedly, the “factory porcelain” in Jiang Jingchen’s collection is of exceptional quality.

During the state-owned era, factories used natural mineral materials, giving the glazes a unique luster and color that wouldn’t fade over time. The state-owned factories and research institutes gathered many masters, some of whom later became national or provincial-level ceramic artists. These fine factory porcelain pieces were born during the peak of these artisans’ careers.

Twenty years ago, the cultural value of “factory porcelain” hadn’t yet been recognized by the public.

In Jiang Jingchen’s eyes, “factory porcelain” holds broader historical significance. As is well known, China’s official kiln system began operating in Jingdezhen during the Song and Yuan dynasties, producing porcelain with the nation’s full resources. Similarly, factory porcelain was created under state leadership, pooling national efforts and using traditional techniques—a unique phenomenon in history.

Jingdezhen fifty years ago was also different from today. The kilns used for firing ceramics transitioned from wood-fired to coal-fired, and with advancements in energy, they were later replaced by gas and electric kilns. Even the kaolin clay used for ceramics underwent physical changes over time.

In the face of relentless progress, these porcelain pieces, along with the craftsmanship and emotions embedded in them, have become a “rich mine” of irreplaceable artifacts.

03 Artworks Repeatedly Validated Hold Universal Value

After giving up her clothing business, Jiang Jingchen returned to Jingdezhen and officially took over “Zhen Yi Tang” in 2016. The porcelain her father had collected to help friends became a career she was determined to pursue.

The philosopher Schopenhauer once said, “The finest works of art, created by the most outstanding talents, should always remain mysterious and unattainable to the masses. They are separated by deep chasms, just as ordinary people can never enter the world of princes.”

The mystery and inaccessibility Schopenhauer spoke of stem from the “chasms” in people’s understanding of art.

The solution is “circulation.” The intrinsic value of “factory porcelain” is undeniable—the original creators used their skills and experiences to create these works. But this is just the starting point. Only by bringing these pieces to the market, subjecting them to repeated validation through auctions and collections, can their value gain universal recognition.

According to Jiang Jingchen’s vision, Zhen Yi Tang is an institution dedicated to promoting factory porcelain. It will prove the irreplaceable value of these long-hidden artworks to modern society.

Working with porcelain and the people who appreciate it in Jingdezhen, Jiang Jingchen never imagined such a dramatic turn in her life.

As she put it, when she first arrived in Jingdezhen, she found the pace of life unbearably slow. When she went shopping with her family, she’d already reached the other end of the street before they’d taken a few steps. Her family joked that this wasn’t shopping at all.

Gradually, she began to understand the dynamics.

The people interested in factory porcelain varied. Some were seasoned collectors who had their own standards and didn’t need much explanation—just seeing the pieces was enough. Those looking for investment opportunities sought long-term or short-term增值收益 and needed reassurance. Building trust required ample inventory and authenticity.

But for those who bought porcelain purely out of love, she had to chat about everything. The reasons for their attachment varied, but many were drawn to the collective spirit of that era—the closeness and mutual care among people.

Having had few friends in Hong Kong, she now found companionship. “It’s actually nice to have human warmth,” she said.

04 Bridging the Chasm: We Are Custodians of an Era

Every artwork has value, but the “chasm” persists.

During an auction on the Dongjia App last August, Jiang Jingchen experienced a “flop.” The piece was a heavy-work famille-rose snowscape double-eared fish-tail vase produced by the Jingdezhen Art Porcelain Factory. The artist, Shen Shengsheng, once served as deputy director of the factory’s art research department. Trained by Yu Wenxiang, a disciple of He Xuren (leader of the “Eight Friends of Zhushan”), Shen mastered traditional famille-rose snowscape techniques. This vase, painted with intricate famille-rose designs, was one of his representative works.

Previously, she had only acted as a middleman, handing porcelain to collectors or auction houses for single-point dissemination. Online auctions offered a new possibility—a piece could reach multiple buyers simultaneously in a short time.

The auction result was disappointing, with the final price only a fifth of its usual value.

She felt it was a pity. This incident highlighted the ambiguity and complexity of artwork value. More importantly, incomplete or asymmetric information about art hindered market transactions. Building understanding and trust required not only time but also continuous efforts to spread awareness.

Jiang Jingchen has been collecting old photos of porcelain factories, buying any she could find on the market.

Through these images, the face of that era gradually became clearer.

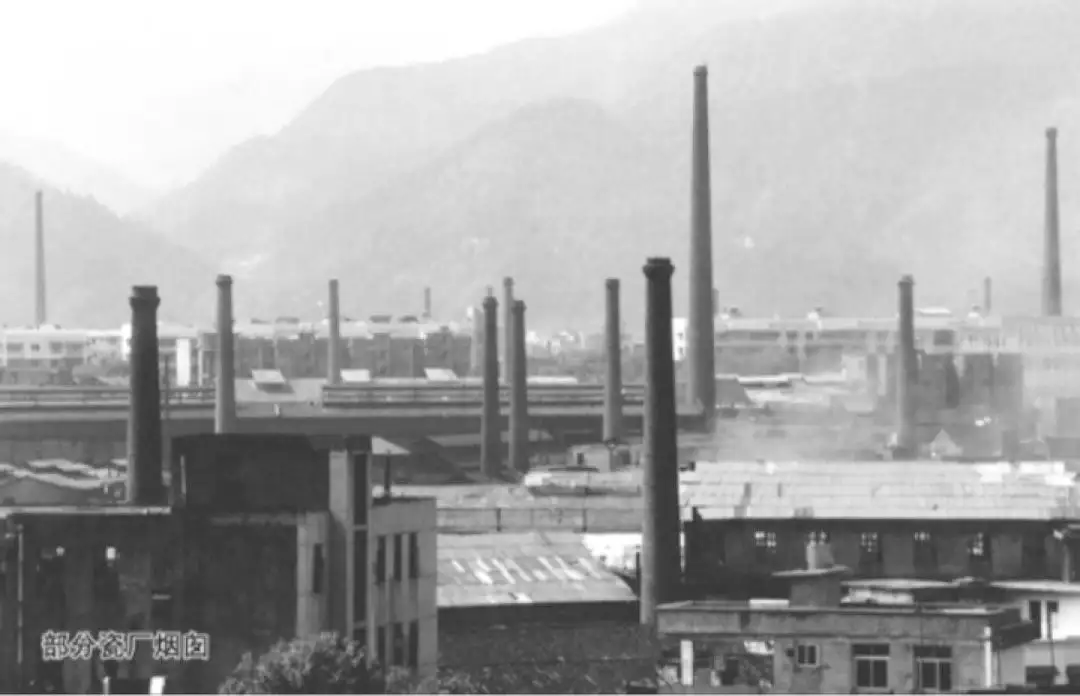

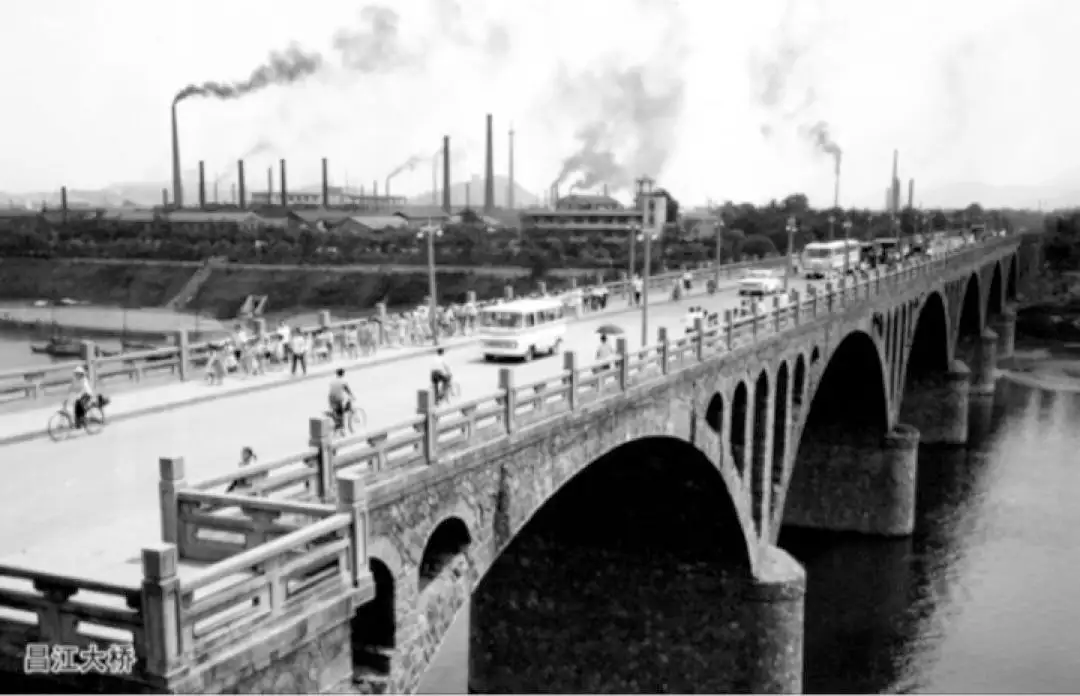

It was a golden age. Artisans who hadn’t yet achieved fame were at their creative peak. People threw themselves into the ceramic industry with unimaginable passion. Every morning, workers rode bicycles into factories scattered across the city. Researchers worked alongside laborers in workshops, kiln masters sweated over roaring fires, and elderly artisans painted intricate designs on massive porcelain vases with steady hands. Whenever people looked up, they saw the city’s skyline dotted with towering chimneys billowing smoke.

The old factory images restored the historical context of the porcelain, ensuring authenticity. On a deeper level, the value of this history would eventually be remembered.

Building museums and holding exhibitions were one approach, but the physical porcelain pieces were even more crucial. The existence of factory porcelain would connect an era, narrating a cultural lineage of aesthetic style and emotional significance. When this trend took off, Jiang Jingchen knew it would realize Zhen Yi Tang’s true purpose.

“We are custodians of an era, and also its porters. Wherever there’s a need, we’ll carry it there.”

On a summer afternoon at three o’clock, Jiang Jingchen took us on a tour of Jingdezhen’s porcelain factories. Her car passed fruit stalls, fish markets, and smokeless chimneys of long-cooled kilns. History vanishes relentlessly, but those who care will always preserve it with unwavering devotion

Deng Xiping: Walking a Long Path No One Has Taken Before

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Deng Xiping: Walking a Long Path No One Has Taken Before

Born in the 1940s, she was a university student cultivated by the nation, and thus, she resolved to use her knowledge to serve her country. Once she embarked on the path of learning ceramics in Jingdezhen, she never looked back. Devoting her life’s knowledge and skills to the production of color glazes was a decision she never regretted.

Her scientific achievements showed people of that era that education was valuable and that women, too, could make industry-shaping contributions in the field of scientific research.

01 The Door to a New World

In the summer of 1965, Deng Xiping boarded a long-distance bus from Nanchang to Jingdezhen. The vehicle rattled endlessly along a muddy road covered in gravel, and the scenery outside grew increasingly desolate. In the sweltering heat of August, the bus had no air conditioning, and her white shirt was soaked with sweat. The closer she got to her destination, the more anxious she felt, as if she were being taken to some remote mountain valley she knew nothing about.

That year, she was 23 years old, freshly graduated from the Chemistry Department of Wuhan University, and assigned to work at the Jingdezhen Ceramics Research Institute under the Ministry of Light Industry. On the map, Jingdezhen didn’t seem far from Wuhan. The student affairs office at Wuhan University had planned her journey: take a boat from Hankou to Jiujiang, then a train from Jiujiang to Nanchang, and finally a bus from Nanchang to Jingdezhen.

The entire trip took three days. To save on the two-yuan daily accommodation fee, she spent one night at Jiujiang Railway Station and another at Nanchang Bus Station. By the time she finally boarded the bus to Jingdezhen, she was utterly exhausted.

Aside from her, there was another boy on the bus who had been assigned to work at a Jingdezhen porcelain factory. When they asked about directions to their respective workplaces, a doctor from the Industrial and Mining Hospital on the bus mentioned that a car was coming to pick him up and offered to take the two students along. When the bus arrived, a vehicle did indeed show up—but unexpectedly, it was an ambulance.

Deng Xiping recalled her first day in Jingdezhen: covered in dust like a clay statue, with her luggage yet to arrive, she rode an ambulance to the Ceramics Research Institute. A personnel officer led her to the girls’ dormitory, arranged for her to take a shower, gave her a change of clothes, and she went straight to bed.

The next morning, she walked around the institute and found the environment surprisingly pleasant—lush trees, flowers, and neatly arranged buildings, nothing like the remote mountain valley she had imagined. Her anxious heart gradually settled. This was her first time away from home and the first stop in her life after leaving campus.

That first year in Jingdezhen remains the happiest in Deng Xiping’s memory.

Five college graduates had been assigned there that year. At the time, the Socialist Education Movement was underway, and many new graduates were sent to rural areas to participate. However, the institute allowed these five students to stay and undergo labor training in its experimental factory. Engineers were arranged to teach them ceramic craftsmanship, and they were assigned to train in every step of ceramic production, completing an entire course in ceramic technology within a year.

As the group leader, she and the others not only worked but also handled the institute’s cultural and propaganda activities. The two female students broadcast daily news at the institute’s radio station, while the male students were responsible for the daily bulletin boards.

Deng Xiping was a highly capable learner. Born into an intellectual family, she had shown remarkable academic talent from the moment she fell in love with studying. She excelled in every subject, especially physics and chemistry.

At Wuhan University, she majored in analytical chemistry, a discipline that emphasized both theoretical and practical skills. During experiments, students were required to design their own procedures, with teachers only verifying feasibility. Success depended entirely on execution. After each experiment, a debriefing session was held where the fastest and best performers shared their methods, while the slowest analyzed their challenges, fostering improved thinking and hands-on skills.

This experimental training enabled her to quickly adapt to new tasks. Though she had no formal education in ceramics, she gained a preliminary understanding of ceramic craftsmanship after just a year of training.

02 From Researcher to Color Glaze Apprentice

In 1966, the five graduates were assigned to different departments. The three boys were sent to research labs as technicians, and the art student was assigned to the art research department. But Deng Xiping was placed in the color glaze group as an apprentice.

▲ Deng Xiping in her early years, learning color glazes from her masters

She couldn’t understand this decision. “Why were the others assigned as technicians, while I had to be an apprentice?” Later, the political director shared a story that finally clarified her doubts.

In 1954, China urgently needed precision instrument manufacturing technology from East Germany, but the latter demanded an exchange for Jingdezhen’s color glaze technology. At the time, precious high-temperature color glazes in Jingdezhen were family secrets, passed down only from father to son, with many on the verge of being lost. The Ceramics Research Institute had gathered some inheritors of these techniques, offering them government jobs to collectively restore the craft.

However, these masters had little formal education. They knew how to prepare glazes but not the underlying principles, making it impossible to compile technical documentation. Thus, the state brought in ceramic experts and engineers from the Shanghai Silicate Research Institute, along with a group of recent graduates and young technicians, assigning each master two students to document the color glaze porcelain production process.

The masters followed ancestral methods, while the students recorded the raw materials used, sent samples to the Shanghai Silicate Research Institute for testing, and documented the entire process—from glaze preparation to application and firing. After six months, a complete set of technical data was compiled.

This document, known as the “Sino-German Technical Cooperation Data,” was exchanged for “East Germany’s Precision Instrument Manufacturing Technology,” contributing significantly to China’s early industrial development. It was the first scientific documentation of Jingdezhen’s traditional color glaze porcelain production, revealing many secrets and paving the way for future learners.

From the 1950s onward, the Ceramics Research Institute selected a few outstanding graduates or young technicians each year to apprentice in the color glaze group. Deng Xiping joined in 1966, becoming part of the last group to learn directly from the masters. At the institute, she studied under masters Nie Wuhua and Chen Honggao.

Her masters taught her to identify raw materials by touch, sight, and even taste. When she didn’t understand something, she would consult library materials. To test firing conditions (temperature, pressure, and atmosphere curves), she had to overcome old superstitions—such as the belief that women entering kilns would cause them to collapse—to install test pipes.

Traditional Jingdezhen porcelain-making involves 72 steps, each affecting the final outcome. She followed her masters to mines around Jingdezhen, recording mineral compositions. They also sourced ingredients from traditional medicine shops, such as pearls, agate, and germanium. Historically, artisans even used gold, silver, and precious stones to create color glazes.

Perhaps it was the unpredictable nature of color glazes that fascinated her. Her relentless pursuit of knowledge helped her endure the hardships of learning.

Deng Xiping was thrust into this niche field of research, unaware that she would spend her entire life immersed in it. This world was boundless, filled with endless questions waiting to be answered.

Glaze is the “clothing” of ceramics. Ancient artisans used white as the starting point and black as the endpoint, expressing their spiritual world through color. Variations in raw material ratios, firing conditions, temperature, and kiln positioning all influence the final hues, creating a dazzling array of colors.

High-temperature color glazes, as an independent form of ceramic decoration, represent one of the earliest methods in history. They focus on the craft itself and the exploration of materials, using natural minerals to create glazes that, after high-temperature firing, form gem-like structures. Known as “man-made gemstones,” they are one of Jingdezhen’s four traditional porcelain treasures.

Due to the uncertainty of kiln changes, the yield of colored glazed ceramics is very low, and the difficulty of firing is very high. In the early Qing Dynasty, during the reigns of Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong, Jingdezhen’s porcelain industry reached its historical peak, and the color glaze also entered its heyday. But at the same time, the royal family imposed strict regulations on the production and use of colored glazed ceramics.

The colored glazed porcelain produced by official kilns during the Ming and Qing dynasties was not allowed to be produced by civilian kilns. If this rule is violated, those who commit serious crimes will be beheaded. According to Volume 161 of the Annals of Emperor Yingzong of the Ming Dynasty, in the eleventh year of the Zhengtong reign (1446), an order was issued to prohibit the private production of yellow, purple, red, green, blue, blue, and white blue and white porcelain by the Raozhou Prefecture in Jiangxi Province. The first offender, Ling Chi, was executed, and Ding Nan served as a border guard from his family’s wealth. Those who knew but did not report it were punished by the imperial court. With strict laws, it ensured the royal monopoly on colored glazed porcelain.

And precisely because of this monopoly, its inheritance has also undergone multiple destructive generational changes. Just like the once prominent sacrificial red glazed porcelain that disappeared in the mid Ming Dynasty, it was not until the Kangxi Dynasty of the Qing Dynasty, under the hard research and exploration of porcelain workers, that the lost copper red glaze firing technology, which had been lost for more than a hundred years, was restored to create Langyao red glaze.

The birth of each glaze color involves dozens of complex minerals, which contain many variable trace elements. It is alive and constantly changing.

You have no way to control it, you can only adapt to it, “Deng Xiping described this special technology as follows. Nowadays, many minerals no longer exist, and finding alternative methods requires a lot of empirical exploration. In addition to studying glaze formulas, there are also many top secret operating techniques involved, which are the inheritance of experience.

She recalled that in 2013, she restored the kiln transformation techniques of the Tang Dynasty’s “secret porcelain” that had been lost for thousands of years and the Ming Dynasty’s “flowing Xia porcelain” that had been lost for 600 years, and successfully developed the “secret glaze flowing Xia cup” on a piece of work through innovative fusion. This success lasted for 23 years, and the hardships involved can be imagined.

▲ Large Bowl of Flowing Clouds

When she was at her wit’s end in the experiment, she would temporarily pause for rest. However, since entering this research, these experiments have been constantly in her mind. As soon as inspiration arises, she immediately starts experimenting. It is this relentless persistence that has enabled her to achieve breakthroughs in both thinking and technology, and to reach the pinnacle of the field of color glazed ceramics.

03 Burn out the “Jun Hong” glaze,

On the day of being commended

If it weren’t for the tempering of the times, Deng Xiping might have quietly worked on his research projects at the Ceramic Research Institute of the Ministry of Light Industry, and then lived a plain life.

But after the founding of New China, it went through many changes. The period of the Cultural Revolution was undoubtedly a dark and bleak time for intellectuals. ‘Stinky Old Nine’ was synonymous with Chinese intellectuals in the 1960s and 1970s, ranking them among ‘local, wealthy, anti, bad, and right-wing’.

In 1968, the research institute was dissolved.

Deng Xiping was demoted to Jiangcun Commune in Jingdezhen. The pain in her heart is that she couldn’t do scientific research during the best time of her life.

In 1972, the demoted cadres were reassigned to their original positions, and Deng Xiping voluntarily went to Jianguo Porcelain Factory. The reason for making such a decision is that she is well aware that the research institute at this time still needs time to recover, but the research cannot wait for a moment. Only Jianguo Porcelain Factory is a nationally designated porcelain factory that produces traditional colored glazed porcelain.

Among them, precious colored glazed porcelain is also a national gift porcelain given by national leaders during their visits and foreign heads of state during their visits to China. The products are sold to more than 120 countries and regions around the world, and the economic benefits are very good.

There was sufficient funding in the factory to support her research. After arriving at Jianguo Porcelain Factory, the technical director requested her to form a color glaze experimental group with two color glaze masters.

They went to collect three tables and started building a new research laboratory in a mud house that was less than ten square meters and had no windows. The factory said that if there is no experimental equipment available, please place an order and have the supply department purchase it.

But many small experimental and laboratory equipment cannot be purchased and require the cooperation of the factory’s metalworking and electrical teams for production. Making equipment is a difficult process that requires the cooperation of electricians, metalworkers, carpenters, and so on. She is the first one to arrive at the factory every day, and if an electrician is needed, she will go to the office of the electrician team and wait for the allocation of workers’ work. Half a year later, the simple laboratory was finally built.

But the challenges had only just begun. The factory respected the veteran craftsmen but was skeptical of college graduates like Deng Xiping. Conducting color glaze experiments required test pieces and clay bodies for trials.

At the time, production line workers were paid by the piece, and they didn’t believe Deng Xiping could succeed in creating color glazes. They often gave her damaged clay bodies for her experiments. Realizing this wouldn’t work, she approached the leader of the molding team and said, “If you give me flawed clay bodies, even if the glaze turns out well, the finished porcelain will still be defective, wasting state resources. If you give me good clay bodies, a successful firing will count toward your production quota, and if it fails, the technical department will issue a note to ensure your team suffers no losses.”

The molding team leader was convinced. He turned around, rummaged through a pile of finished clay bodies, and finally handed her two of the smallest ones. She thought these two clay bodies were hard-won and decided to create a color glaze that the Jianguo Porcelain Factory had never seen before—one she was confident in. In the end, she chose to recreate an orange-yellow crackle glaze she had worked on before.

Her experience in the factory had taught her that she had to handle everything personally. Once, she had placed test pieces in a specific spot in the wood-fired kiln, but when the kiln was opened, the pieces had been moved, greatly affecting the results. This time, she watched as the kiln worker placed the clay bodies in their designated spots before leaving. When the kiln was finally opened, both pieces were intact, covered in a vibrant mango-yellow glaze with large crackle patterns.

The molding team leader was overjoyed. He took the two bottles to the production department, where the leaders were astonished and praised him, saying, “The molding team can even produce new products now!” When asked who had made them, the leader replied, “Deng Xiping from the color glaze team.” From then on, the craftsmen began to cooperate with her, believing in her ability to excel in color glaze research.

In 1973, the Jianguo Porcelain Factory’s flagship product, the “Jun Red Vase,” shifted from hand-molding to slip-casting, which improved production efficiency. However, the Jun red-glazed porcelain that came out of the kiln was all cracked, forcing the entire color glaze workshop to halt production.

The “Jun Red Vase” was the Jianguo Porcelain Factory’s most profitable product. To solve this technical issue, the factory held daily meetings to brainstorm solutions.

The root of the problem lay in the fact that after the molding process was changed, the weight of the clay body was halved, making it too thin to withstand the stress caused by the Jun red glaze’s crackling. This caused the clay body to crack and the vases to break. However, the factory insisted that switching from hand-molded to slip-cast bodies was a technological advancement that couldn’t be reversed. The solution had to come from modifying the glaze, so the responsibility fell on the craftsmen in charge of the Jun red glaze. But after two months of testing, no breakthrough was made.

As the first state-owned porcelain factory in Jingdezhen and the mother factory of the “Ten Great Porcelain Factories,” the Jianguo Porcelain Factory faced severe production losses that couldn’t be justified to the state. The factory began seeking help from experienced craftsmen across society to solve the problem.

At the time, Deng Xiping’s task was to assist these craftsmen with their experiments. People came forward with suggestions in droves, keeping her extremely busy. Most of them approached the problem by trying to reduce the crackling in the Jun red glaze, but the modified glaze either continued to crack or failed to produce the red color, leaving the issue unresolved.

Deng Xiping remembered one bearded craftsman who said, “I have a family heirloom called ‘calming powder.’ If you apply it to the clay body before applying the Jun red glaze, it won’t crack.” She thought that if this powder worked, it could solve the problem, so she insisted on conducting multiple tests.

In the end, the calming powder failed, but the old craftsman gave Deng Xiping an inspiration: she needed to approach the problem differently and think outside the box.

She suddenly thought of a balloon. If you poke a balloon with a needle, it pops. But if you try to squeeze it with both hands, it’s much harder to burst. The reason is that the force is distributed evenly. In other words, if they couldn’t stop the Jun red glaze from cracking, perhaps they could make it crack more—but in a fine, dense pattern that would distribute the stress evenly, preventing the vase from breaking. This was the power of reverse thinking.

With this idea in mind, she discarded the original test formula and developed a new one based on her new approach. The test pieces soon exhibited a spiderweb-like crackle pattern. The production supervisor overseeing the tests immediately took the samples to higher-ups, and the technical director affirmed the new direction. He asked Deng Xiping what support she needed for larger-scale trials. She requested a week to produce five test vases.

To meet the deadline, she worked day and night, personally completing every step of the process and placing the pieces in three different wood-fired kilns for testing. A week later, all five vases emerged from the kiln intact. She was overjoyed, and everyone felt hopeful that the production crisis could finally be resolved.

Given the urgency, the factory skipped the pilot production phase and assigned the color glaze research team to oversee full-scale production. Production was no joke, however. The team leader, Master Zuo, was cautious and reminded Deng Xiping that this involved significant manpower, resources, and multiple steps requiring worker participation. With over 80 workers involved in the workshop, any misstep could lead to serious consequences.

To ensure smooth operations, they formed a Jun red production leadership team. The existing Jun red glaze materials in the workshop were sealed and labeled by both the technical and security departments. New materials for the revised formula were sourced directly from the supply warehouse.

Forty-eight hours later, a small portion of the prepared glaze was divided into three sealed containers and distributed to the experimental team (marked for identification), the technical department, and the security department for record-keeping. The rest was handed over to the workshop for production. As the kiln-opening day approached, Deng Xiping grew increasingly anxious, losing sleep over fears that something might go wrong.

On the day of the kiln opening, all the factory’s leaders gathered on-site. When the saggars were opened, the entire room held its breath. As each piece was revealed, not a single vase was cracked. The room erupted in prolonged applause that seemed to never end.

The success became a sensation in Jingdezhen. The factory convened a technical debriefing session for mid-level and above cadres, a day Deng Xiping would never forget. During the summary, Technical Director Yu Changsong remarked, “Education is still useful.” These words moved Deng Xiping to tears, as the stigma of intellectuals being labeled the “stinking ninth category” had not yet faded.

The statement held profound meaning for her—it was a moment when the value of intellectuals was acknowledged. From that day on, the factory’s leaders and workers changed their perception of her. No longer would she be excluded from color glaze research due to being an outsider, a woman, young, or lacking a family legacy. From then on, she could focus wholeheartedly on her work at the Jianguo Porcelain Factory.

Kiln transformed flower glaze seven spiral bottle

In 1978, the National Science Conference was held, affirming the social status of intellectuals. Jingdezhen resumed its professional technical title evaluations, which had been suspended for over a decade. Deng Xiping became one of the first 40 engineers promoted in the city—the youngest and the only woman among them.

04 guarded the dismantled research institute

Carrying weight forward

In the spring of science, Deng Xiping’s mind was completely liberated. After years of research and practice, she realized that researchers must tightly integrate science and technology with production. Intellectuals and workers had to collaborate, and research outcomes required workers’ assistance to be applied in production and achieve significant impact.

She overcame numerous technical challenges. In 1978, her project “Using No. 0 Diesel to Fire Jun Red Glaze” won the Jiangxi Provincial Major Scientific and Technological Achievement Award. Through this project, she developed the No. 62 lead-free Jun red glaze, breaking the historical rule that copper-red glazes couldn’t achieve their color without lead. This innovation pointed the way toward eliminating lead from all color glaze formulas, freeing workers in the field from the threat of lead poisoning and creating immense social benefits.

In 1985, her “New Formula for Large-Scale Lang Red Glaze” won the National Award for Scientific and Technological Progress. In 1989, her “Ceramic Rainbow Glaze” project earned the National Invention Award, and in 1990, her “Rainbow Glaze Artistic Porcelain Plates” won the Gold Medal at the Brussels Eureka World Invention Expo.

After 1984, Deng Xiping served as deputy director and chief engineer of the Jianguo Porcelain Factory. Building on the experimental team, the factory officially established the Color Glaze Research Institute. New products and processes emerged continuously, driving rapid advancements in the development and production of color-glazed ceramics.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the “Three Suns” glaze alone was presented as a national gift to foreign leaders and dignitaries over 40 times. These were the Jianguo Porcelain Factory’s most glorious years. However, as reform and opening-up deepened and the market economy developed, the state-owned factory system revealed many flaws, such as inefficiency, lax management, low productivity, and severe waste.

At its peak, the Jianguo Porcelain Factory employed over 3,700 people, but only about 1,000 were frontline production workers. The factory faced mounting losses, and in the months before restructuring, it couldn’t even pay salaries. Reform of state-owned enterprises was imperative.

In October 1995, the Jianguo Porcelain Factory underwent restructuring, transforming from a single state-owned entity into over 40 independent economic units. These units were contracted by responsible individuals who used the factory’s existing facilities and equipment to organize production. The workers in each unit had to support themselves. Contractors were required to have a sense of social responsibility—they couldn’t lay off employees or reduce wages.

The first batch of contractors consisted of morally upright individuals with leadership capabilities, mostly workshop directors and Party branch secretaries, along with some well-respected team leaders. As a factory leader, Deng Xiping had to implement national policies. By the time of the restructuring, she was already 53 years old.

Her heart was filled with reluctance and helplessness, but what pained her most was the thought of abandoning the research institute she had built with her own hands.

At the time, neither the institute’s Party secretary nor its director dared to take on the contract. The researchers were mostly older, with higher salaries, and had been away from frontline production for years. The institute had no production workshops or equipment of its own. Taking on the contract meant producing goods to sustain themselves, which posed significant challenges. However, everyone was passionate about color glaze research and unwilling to leave the institute.

As the supervising director of the research institute, Deng Xiping couldn’t eat or sleep over the contracting issue.

At her age, she could have chosen early retirement, and many private companies had offered her jobs. But she knew that if the research team disbanded, Jingdezhen’s only color glaze research base would be lost. Ongoing projects would halt, the development of traditional color glazes would be delayed, and rebuilding the institute in the future would be extremely difficult.

She couldn’t abandon these research achievements and walk away alone, so she had no choice but to lead the institute forward.

Thus, under exceptionally difficult circumstances, she embarked on a second entrepreneurial journey in her life. She and her husband had worked in state-owned units their entire lives and had little savings, with two children in university. She and the research team had to rely on pooled wages and loans based on her reputation to raise operating funds and weather the difficult startup period.

Without equipment, Deng Xiping leveraged her good reputation and connections to borrow materials and machinery from other units in the factory, repaying the debts in installments.

Without a workshop, the factory allocated a 200-square-meter abandoned oil storage space as their production site. A 50-ton oil tank still sat atop the space, and removing it required a crane rental costing 1,000 yuan—a sum the factory couldn’t afford. Deng Xiping persuaded a friend to purchase some of the factory’s stockpiled porcelain to raise the money for the crane.

The new entity set up a makeshift workshop in just eight days. Deng Xiping recalled racing against time, competing with the market.

Without a kiln, Deng Xiping arranged to fire their porcelain at the Nanguang Ceramics Company. During this period, a group of former researchers pushed carts loaded with clay bodies from Shengli Road to Shuguang Road in Jingdezhen.

At the time, the “Three Suns” product was the best-selling on the market, with first-grade pieces fetching 420 yuan each and high demand. For the research team, producing “Three Suns” wasn’t technically difficult, but many researchers hadn’t personally worked on color-glazed porcelain in years, having mostly supervised workers. There was a big difference between guiding others and doing the work oneself.

As a result, they encountered numerous issues in the production process. Additionally, since they relied on borrowed kilns, they couldn’t control the firing quality. In the beginning, almost none of their “Three Suns” pieces met first- or second-grade standards, and even third-grade pieces were rare. Most were unsellable fourth-grade or worse.

San Yang Kai Tai Flat Belly Bottle

“When it rains, it pours.” While waiting for funds to purchase materials and pay salaries, their porcelain kept turning out poorly. Yet instead of blaming each other, they sat down together to analyze the problems, encouraging one another to overcome the challenges.

For the first three years of the contract, the entire team worked without a single weekend or holiday off. Any profits went immediately toward repaying debts, followed by ensuring employees’ livelihoods—their wages had to match societal standards to keep them motivated to continue developing new products and researching.

Other companies came to poach their workers, but not a single person left Deng Xiping’s team before retirement. Reflecting on those days, Deng Xiping recalled the hardship, the setbacks, and the struggles, but she also saw it as a rare and valuable life experience. After three years, the debts were cleared, and the situation began to improve. Once solely focused on research, she was now forced to learn marketing, face the market, set prices, and promote products.

She realized how difficult it was to conduct research in an open market environment—it required human, material, and financial support to go far. She was grateful she had persevered. Without this base and this team, color glaze research would have undoubtedly been delayed.

In 2010, with the support of the Jingdezhen municipal government, Deng Xiping established the Deng Xiping Ceramic Art Gallery and the Jingdezhen Color Glaze Ceramic Art Research Institute. In 2013, she founded the Jingdezhen Mingfangyuan Deng Xiping Ceramics Co., Ltd., which features a 2,400-square-meter exhibition hall displaying over 1,000 types of color-glazed porcelain she developed or innovated over 50 years. This created a new platform for cultural exchange and display of color-glazed porcelain art, now attracting over 10,000 visitors annually for tours and study.

Thinking about heritage, she called her daughter, a graduate of Southeast University, back to her side to personally teach her the craft of color glazes. Her daughter now shoulders the task of sharing color glaze knowledge with the outside world, encouraging more young people to join the ranks of research and inherit.

That day, when we met her, the originally scheduled two-hour interview stretched into five hours. She spoke so passionately that she even forgot to eat, only stopping after repeated reminders from her staff.

She reminded me of a line from the movie Forever Young: “What this era lacks is not perfect people, but those who act with sincerity, justice, fearlessness, and compassion from the heart.”

Born in the 1940s, she repeatedly emphasized that she was a college student cultivated by the nation and thus must use her knowledge to repay the country. Applying her lifelong scientific knowledge and skills to the production of color glazes was a decision she would never regret.

Over half a century, she innovated more than 40 types of color glazes and replicated over 1,000 traditional color-glazed porcelain varieties for production. Her research on the “hidden floral patterns in kiln-transmuted glazes” led to the creation of entirely new glaze types like “Phoenix Feather Glaze,” “Feather Silk Glaze,” “Plume Glaze,” and “Rainbow Glaze,” elevating Jingdezhen’s kiln transmutation technology to unprecedented heights.

Looking back to 1965, the road from Wuhan to Jingdezhen—no one could tell her what lay ahead, for they had never walked it. How far the road stretched, only she would know by taking step after step. Though the path ahead was unclear, walking it allowed her to see her own heart and find her direction.

From youth to white hair, dedicating her youth and passion to scientific research—this was the long road she chose to walk. She walked it, so those who came after could see the light.

Cool Banana: Living Slowly, Crafting Slowly

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Cool Banana: Living Slowly, Crafting Slowly

This couple once went viral online under the headline: “A Korean and a Jilin Native Became a Ceramic-Making Power Couple at the Foot of the Mountain.” Countless comments read, “This is the life I want.”

Guided by this “dream life” filter, we arrived at the Foot-of-the-Mountain Village, where time at Cool Banana Studio bears witness to the couple’s unique “life force.”

Kim Soohyun and Zhong Heng are entering their eighth year as ceramic artists. Their approach to creation follows an ancient, unhurried rhythm—one that has forged an unshakable resilience, insulating them from the era’s relentless tides.

Standing firmly by one’s convictions isn’t easy; challenges abound. But relax—solutions always emerge.

01 The Korean Girl Who Came to Jingdezhen for Pottery

Crafting Utensils Born from Daily Life

“In 2003, I traveled to Africa. Our guide, also African, would gather the group—tourists from various European countries—each morning by shouting, ‘Cool Banana!’ We’d all cheer, ‘Yeah!’ And so the day began.”

Kim Soohyun’s Mandarin is excellent. Though occasional tonal slips betray her non-native roots, these quirks lend her storytelling an oddly persuasive charm.

“Cool Banana” carries layered meanings. To her, it embodies a “let’s-start-the-day” mindset—adventurous, curious, and buoyantly adaptable. “Everyone laughs, today is happy.”

She offers a childlike analogy: “Look at a banana—it’s shaped like a smile. A big smile.”

Before, Kim was a quintessential Seoulite—university-educated, downing four or five daily coffees. She thrived on urban convenience: cafés, galleries, and parks at every corner, sparking endless inspiration.

Jingdezhen, at first glance, stunned her.

Though she’d lived in Beijing and Shanghai, moving to Jingdezhen for a ceramics master’s was always the plan. For Korean potters, most market offerings hailed from Korea or Japan. Occasionally, she’d spot pieces stamped “Made in Jingdezhen, China”—a holy grail for ceramists. “So I went,” she says.

Her early days were disorienting. No subway, unreliable buses (she jokes, “Wherever people queued was the bus stop”), and a glaring lack of coffee gear. Despite Jingdezhen’s ocean of teaware, she found no proper coffee cups. Even classmates focused on tea sets. So she made her own: drippers, mugs, then plates.

Zhong Heng, her classmate-turned-partner, knew her coffee habits well. The soft-spoken Jilin native balances her whirlwind ideas with meticulous planning. Their first collaborative line—striped tableware—emerged from personal need.

Compared to intricate blue-and-white or famille rose techniques, stripes seemed rudimentary, almost “too plain” amid Jingdezhen’s ornate tea sets. But the couple obsessed over subtle textures. “We tried carving, painting—finally settled on hand-scored lines. Molds feel lifeless; hand-rolled clay has better weight.”

02 Holding onto Freedom

Requires Luck and Help

Creating was one thing; selling, another.

Back then, Jingdezhen’s market split between high-end teaware (valued for craftsmanship and名家 scarcity) and bulk-produced daily porcelain. Cool Banana’s work fell into a niche no-man’s-land.

Summer 2012, friends nudged them to join the fledgling “Pottery Workshop Market,” founded by Hong Kong ceramist Zheng Yi to support young artists. “We had no clue—when to go, how to set up,” they recall, laughing. That morning’s sales: 600 yuan. “We were over the moon.”

More crucially, Zheng Yi became their first buyer, purchasing the striped set. Her endorsement—a vote for bold self-expression—fueled their confidence.

The stripe series evolved over seven years: cups, plates, teapots—all minimalist, geometric, life-centered.

Their second line, “Powder Blue,” was inspired by Korean folk paintings during a Seoul visit. Traditional Korean buncheong ware, gray clay brushed with white slip, features playful patterns—floral scrolls, clouds, raindrops—aligning perfectly with Cool Banana’s ethos.

Seven years in, Jingdezhen’s art scene, though no match for megacities, has given them something rarer.

“This crumbling city holds surprises,” Kim says. Its collectivist-era assembly lines may be defunct, but the masters remain. “Nowhere else—not Beijing, not Shanghai—has this concentration of world-class artisans,” Zhong adds. “That’s why foreign artists come: they find collaborators here.”

03 Moving Forward

Amid Life’s Beautiful Chaos

Two years ago, they relocated to Foot-of-the-Mountain Village, a former porcelain hub so obscure even locals barely know it.

Sunlight floods their studio, where two long tables display an array of wares. A mint-green armchair, coffee bar, and plants create a café-like nook—utensils used daily in life’s small rituals.

Parenthood brought “friction”—life’s cozy blanket now pilled with challenges. “We’re a two-person operation; neither can slack,” Kim says. Her free-spirited rhythm shattered initially. Naptimes became frantic sprints between home and studio. “That little one drove me mad.”

They scaled back output, dropped clients, and weathered the storm. Now, 8:30 AM to 5:00 PM is studio time—then it’s childcare. “Turns out, separating work and life works,” Zhong shrugs.

Their synergy endures: Kim dreams up ideas; Zhong troubleshoots. “We influence each other,” he says. Late-night fixes are common: “Once, I spotted an unfinished teapot handle at midnight—had to fix it right then.”

Meals are simple—sautéed spinach, braised fish. Their early plates, designed for pasta, now accommodate Jingdezhen’s homestyle dishes.

Some urge them to scale up, collab with platforms, or market a lifestyle. Zhong demurs: small-batch ceramics are their forte. “Life unfolds slowly; pottery takes time. Solutions come eventually. Those suggestions? We’ll see.”

Q&A with Cool Banana

Q: Do your work styles differ?

Kim: Totally. I need freedom—work when inspired, rest when not. He can’t stand that. But both ways have merits. My best ideas come in relaxed settings.

Q: How has parenthood changed your workflow?

Zhong: Pre-baby, we’d work past midnight. Now, with pickup at 5 PM, we’ve learned to focus. It’s healthier.

Q: As a Korean in China, what’s your take on young Chinese preferring Japanese/Korean ceramics?

Kim: China’s daily ware is excellent, but handmade pieces lack mainstream acceptance. We’ll keep at it—more need to know us.

Q: Why stay in Jingdezhen?

Zhong: Where else gathers the world’s top talent? The openness is unmatched. Try visiting a random factory elsewhere—awkward. Here, glaze sellers want you to know their products. Everyone shares knowledge eagerly.

Luo Xiao: Elevating Survival into an Art of Living

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

Luo Xiao: Elevating Survival into an Art of Living

Born in 1986, Luo Xiao possesses a composure beyond his years, as if the temperament of an artist flows inherently through his veins. At 16, he apprenticed under Guo Wenlian, a professor at Jingdezhen Ceramic University, embarking on a path that merged theoretical study with hands-on ceramic craftsmanship.

Three years of rigorous training laid a solid foundation for his future independent design brand, “Xiang Shang.”

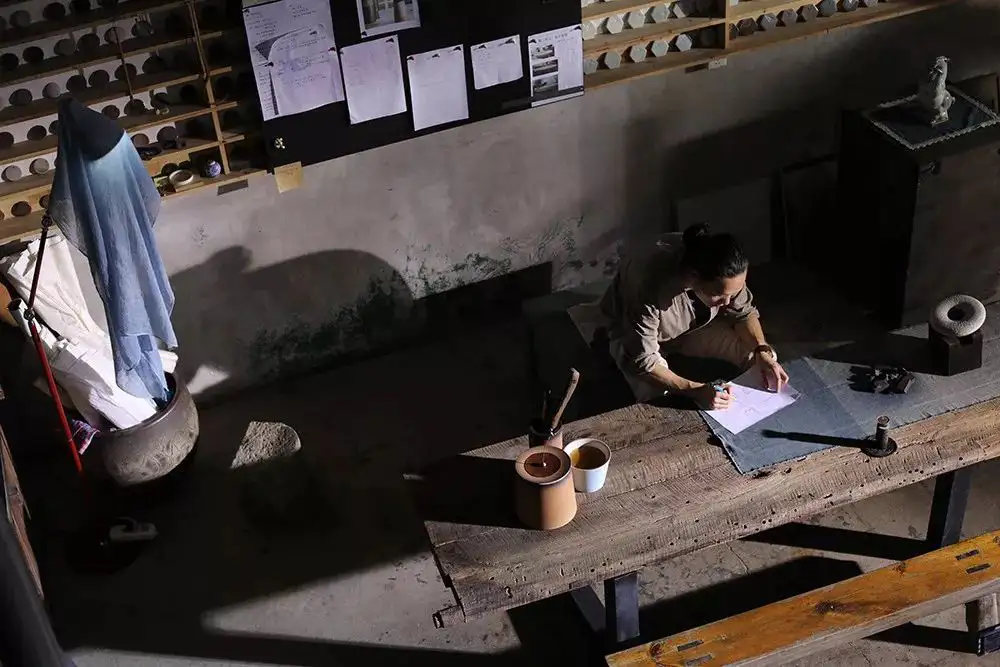

In Sanbao Village, not far from the ancient kiln sites of Hutian, a narrow, unmarked dirt path winds upward past a succulent greenhouse to Luo Xiao’s Xiang Shang Studio.

Once a derelict factory, the site was overgrown with weeds and inaccessible when Luo Xiao first arrived. He and his brother rolled up their sleeves to transform it: preserving the old windows and yellow brick walls, painting the interiors green, and repairing the wooden roof while leaving a skylight for sunlight to stream in.

The courtyard was redesigned too—the towering trees remained, but now accompanied by outdoor dining decor and a Dogo Argentino that roams the village. On the slope, Luo Xiao built a cozy guesthouse for visiting friends. Over time, the studio “filled up”: workout rings, a dramatic test-tile wall, works crowding the tables…

Here, they throw pots, glaze, play music, host weddings, and watch the World Cup under the stars.

Amid this fusion of life and nature, Luo Xiao ponders boundless ideas. His thick sketchbooks are crammed with designs—some meticulously detailed with measurements, others just fleeting sketches with scribbled notes. A few evolve through repeated refinement into rational products that return to everyday life.

For many, survival is a heavy burden. But for Luo Xiao, it’s a cycle: drawing from life, reinterpreting it through thought and design, and reintegrating it as poetry—an elevated way of living.

01 The Last Apprentice

With long hair tied back and a plain T-shirt, Luo Xiao resembles a cutting-edge design school graduate. Yet behind his sleek creations lies the discipline of Jingdezhen’s most traditional apprenticeship.

In 2002, the 16-year-old Luo Xiao boarded an overnight train from Nanchang to Jingdezhen after high school. Arriving in the pitch-dark, crumbling streets, he felt uneasy as his introducer dumped his bags at Professor Guo’s home.

“Genuine, solitary, slow to bloom”—these are the words Luo Xiao uses for himself.

His introversion sharpened his senses. He recalls waking the next morning to autumn sunlight piercing his room’s window, the anxiety melting away. The immersive craft culture, unfamiliar yet addictive, felt like stepping into a new world.

He met Professor Guo Wenlian of Jingdezhen Ceramic University.

While peers attended college, Luo Xiao chose apprenticeship—becoming what he calls “Jingdezhen’s last true disciple.” Living in his master’s home for two and a half years, he endured strict training blending traditional ceramics with academic art fundamentals, covering everything from daily chores to pottery-making.

“It felt like a young monk studying under an old Zen master.”

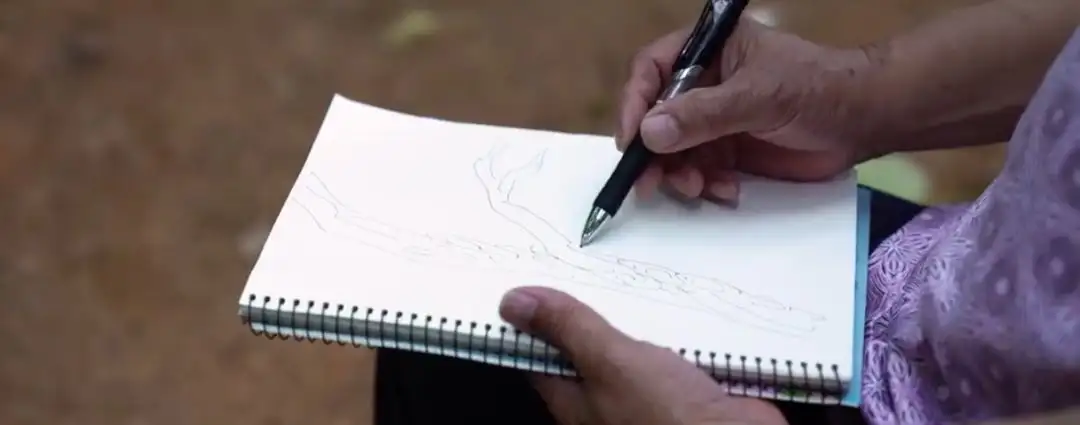

Starting from zero, he practiced sketching daily in the garden, reviewing his work with Guo. Among the master’s disciples, Luo Xiao wasn’t the most gifted but was the most diligent—rising earliest, sleeping latest.

Beyond study, he handled household tasks: cleaning, grocery prep, hauling goods. Acid rain from Jingdezhen’s industrial pollution meant weekly fish tank maintenance. These chores were inseparable from traditional apprenticeship.

Later, Luo Xiao assisted Guo in design research, liaising with factories and conducting glaze experiments. “My master’s rigor—in work and ceramic philosophy—shaped me profoundly. Those three years were beautiful because of his guidance. Leaving was necessary, though. I needed to test myself in the real world.”

▲ Luo Xiao’s works

Despite his master’s shelter, Luo Xiao craved broader horizons and eventually set out on his own.

02 Experimenting with Color Glazes

When Luo Xiao first moved his studio to Sanbao, there was no path up the hill—he and his brother carved one themselves. Their chosen focus, color glazes, was a high-barrier technique demanding endless trials, seldom pursued by the young.

In Jingdezhen’s lexicon, color glazes are traditional. “One glaze on 18 test tiles, fired in different kiln spots, yields 18 hues—that’s the magic. Half human effort, half heaven’s will.” Luo Xiao was hooked.

Earlier, he’d worked at factories in design and management roles, even learning glassmaking. But when design was reduced to mere drafting, he quit.

Drawing on glaze experiments with Guo and factory experience, he plunged into color glaze research, aiming to modernize tradition for contemporary aesthetics.

▲ Color glaze series

In 2008, Zheng Yi’s Pottery Workshop launched the Loft Market to nurture young ceramists. Luo Xiao calls his early independence “sprouting.” Amid the market’s chaos, he observed, participated, and gradually found his voice.

From design to glaze formulation, he did it all.

Luo Xiao chose the toughest path: high-temperature color glazes. Unlike other ceramic arts, this demands relentless testing—thousands of trial tiles. Painstaking and dull, but his apprenticeship had prepared him.

Initially, he worked intuitively, rarely repeating designs. Like artists with “clean-freak” tendencies, each piece was unique.

He reveled in the process, even the suspense of kiln openings. Failures didn’t faze him—they bred surprises, like his accidental “bubble glaze.” At first, the lumpy texture repelled him, until he cracked a bubble to reveal unexpected colors.

Thus, he salvaged the “flaws” into new creations.

Kiln transformations conjured seascapes, volcanoes, galaxies—but these were no accidents. They emerged from countless attempts. His palette shifted from grays to vibrancy as life brightened. Every piece was an honest dialogue with clay.

His studio is a meticulous archive: shelves of jars hold semi-finished or “failed” works—diaries of his journey.

03 Utility Ware as Altruism

At markets, his “imperfect” pieces sold inexplicably well. Requests poured in: replicas, bulk orders. His first commission—600 handmade cups at 8 yuan each—meant sleepless weeks of trimming, drying, and glazing.

This pushed him toward standardization, a painful pivot.

Professor Guo noted in an interview: “Many pursue fame or profit in ceramics today. Luo Xiao’s choice—anonymous utility ware—is unglamorous. For a young artist to persist, handling everything from form to glaze alone, is rare. His grasp of ceramics is holistic.”

To focus on design, Luo Xiao recruited his brother.

“I was ‘tricked’ here,” laughs Luo Hua. “I had a comfortable life in Tonglu—great scenery, good pay. But his vision for a lifestyle brand blending color glazes with functional ware convinced me to join.”

▲ Left: Luo Xiao; Right: Luo Hua

In 2013, they launched Xiang Shang, creating wares that express ceramic’s vitality through the five elements (metal, wood, water, fire, earth) and the interplay of curves and angles.

Luo Xiao chose utility ware as an act of giving. His muse, Lucie Rie, once said: “Hands impart soul; let the work speak. No sentimentality, no theory—just serene beauty. Nothing needs overstatement, neither pots nor life.”

He too seeks soulful objects.

One incense holder subverts stability—its movable structure holds 31 sticks (one month’s worth), each burning for 15 minutes, inviting users to contemplate time.

Recently, Luo Xiao has evolved for Xiang Shang’s sake. Once a workaholic oblivious to anything beyond clay, he’d famously forget his wallet. Now a brand owner, he struggled to balance family, creativity, and business, veering into obsession or escape.

He’s learning to separate art from product, shifting from solo craft to structured production. Standardization is inevitable—products demand consistency in form, function, and beauty.

A trapezoidal cup took five years of tweaks. For an incense burner’s water reflection, he engineered a mixed-material base, down to the circuitry.

“Every functional form endures many mistakes before success.”

Avoidance, he realized, didn’t buy creative time—it bred inefficiency.

So he leans in. One evening, he played music at home. His daughter proposed a dance party. In the dim light, drinks in hand, the rhythm moved him—a rare moment of letting go. The next day, their bond felt deeper.

Now, family time fuels his work. “The essence of things lies in their nature,” he reflects. “What distinguishes people is perception.”

He hopes Xiang Shang inspires lifestyles, awakening fresh ways to feel alive.

A Father and Son’s Unwavering Journey

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

The Story of Jingdezhen Porcelain Painting: A Father and Son’s Unwavering Journey

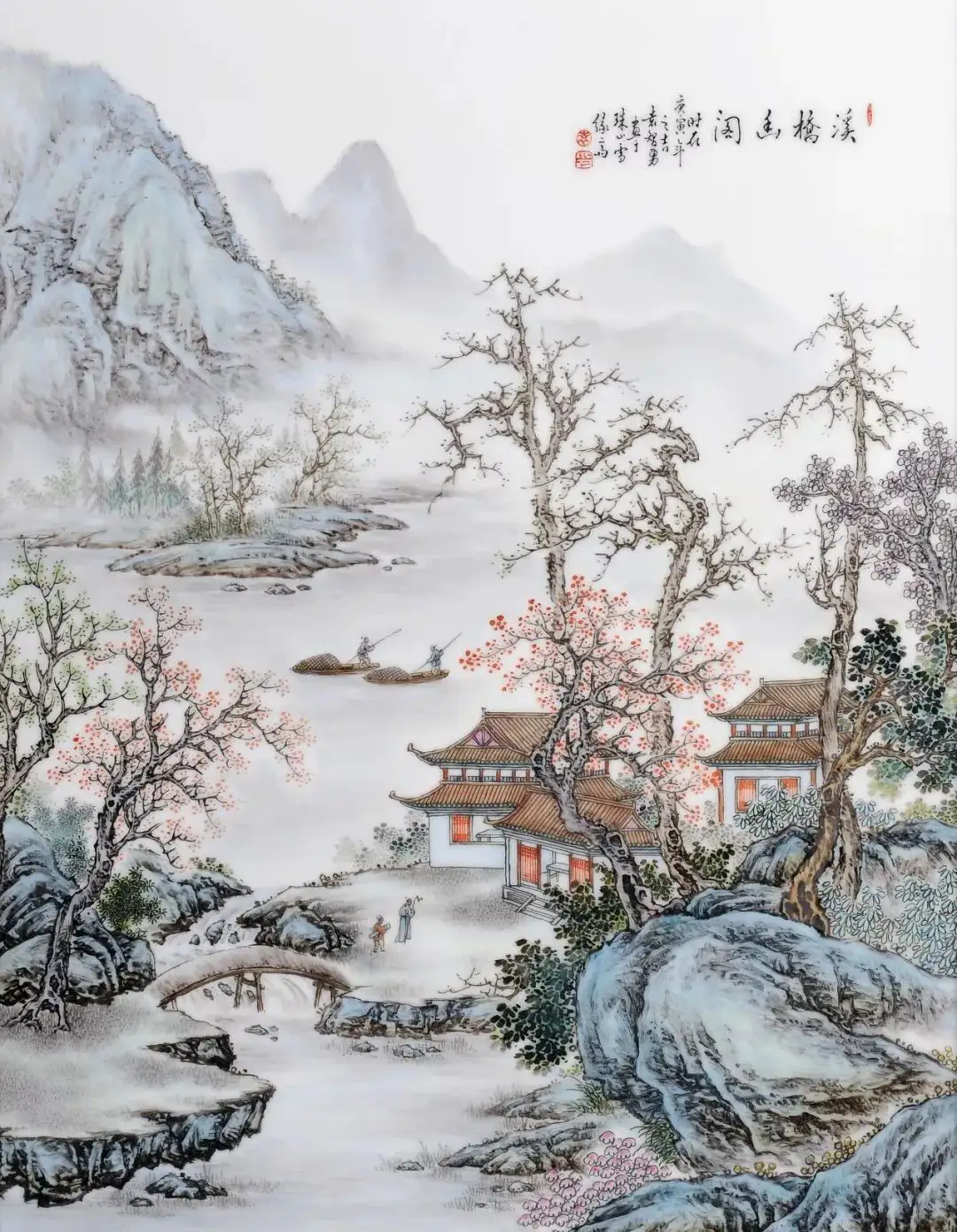

Yuan Shiwen specializes in snowscape porcelain painting—a niche art form in Jingdezhen.

He has devoted most of his life to this craft, and today, his works serve as the “textbook” for snowscape porcelain painting in Jingdezhen. The figure working upstairs, meanwhile, has become a source of inspiration for his son, Yuan Zhiyong.

Father and son have carried this tradition forward, their footsteps never pausing.

Yuan Zhiyong still remembers the essay he wrote about his father in fifth grade. That year, his father, Yuan Shiwen, had just become the director of the Art Porcelain Factory. To him, his father was a hero—except this hero wielded a paintbrush instead of a sword.

Yuan Shiwen paints snowscapes on porcelain, a rare technique in Jingdezhen that combines painting with craftsmanship. The style was pioneered during the Republic of China era by He Xuren of the “Pearl Mountain Eight Friends” and later refined by his disciple Yu Wenxiang. As a descendant of Wang Yeting, another member of the Pearl Mountain Eight Friends, Yuan Shiwen initially studied the Wang School’s blue-green landscapes before receiving guidance from Yu Wenxiang, the “Snowscape King,” mastering an impeccable technique.

His father was deeply responsible, never letting his family suffer. Even as factory director, he tirelessly took on commissions, both to support the household and hone his skills. Late at night, when Yuan Zhiyong got up to use the bathroom, the first floor would be silent except for the whirring of a single oscillating fan. Upstairs, however, a light would still be on, accompanied by faint rustling sounds—his father painting in the attic, careful not to disturb the family. By dawn, he would already be gone again.

Later, as he grew older, Yuan Zhiyong set up his own studio downstairs.

01 Learning to Paint: Strictness Has Its Merits

Yuan Shiwen began painting at nine. The eldest of five children, he started working early to ease his parents’ burden. While other children played after finishing homework, he painted. “What’s there to play with? Asking for a beating?” he recalls.

Wang Yeting was his great-uncle, so the family practiced the Wang School’s landscape style. His father was strict. “Back then, I painted at home in winter without heating. My hands would turn red from the cold, and if he saw me slacking, he’d whip me until I bled,” he says.

Then he laughs. “But being strict was good. My solid foundation owes a lot to that discipline.”

At the time, the family lived near the Imperial Kiln in Xiaosu Alley. Yuan Shiwen would sit outside under a makeshift awning to paint. Yu Wenxiang lived just a hundred meters deeper into the alley. Noticing the boy’s dedication, Yu asked, “Want to learn snowscapes?”

“I had no idea who he was at first,” Yuan Shiwen admits. “Later, I learned he was He Xuren’s star pupil—the undisputed ‘Snowscape King’ of the Art Porcelain Factory’s design studio.”

Yu Wenxiang was unassuming but groundbreaking. Trained by He Xuren, he mastered snowscapes while daring to break conventions. In his Treading Snow in Search of Plums, he abandoned the popular segmented composition for a “high-distance” perspective, drawing the viewer’s gaze deeper into the scene.

Thus began Yuan Shiwen’s dual apprenticeship: Wang School landscapes from his father, He School snowscapes from Yu Wenxiang—a dual artistic nourishment.

In 1962, his ailing mother secured him a job at the Art Porcelain Factory. At 16, Yuan Shiwen both colored and painted. His speed and diligence earned him triple the average wage. But two years later, during workforce cuts, he transferred to the Yuejin Porcelain Factory’s design studio. By year five, he was promoted to workshop chief, and by 30, deputy director.

“When I became director, my father was quietly proud,” Yuan Shiwen recalls. “He was ill then. When people told him, ‘Your son’s the director now,’ he just smiled. He never showed much emotion.” To Yuan Shiwen, his father was a silent but pivotal figure—a man who, like him, had endured harsh training under Wang Yeting as a child. Seeing his son master the Wang School and achieve social standing brought hidden joy.

02 Craft Demands Unending Practice

In the 1970s, the Arts and Crafts Factory needed designers and recruited Yuan Shiwen. To him, those were the most hopeful days—skill commanded respect and ensured a good life for his family.

“Back then, we had no AC, just one floor fan for sleeping. In summer, I’d paint through the heat, wiping myself with a wet cloth. My family slept downstairs, while I worked upstairs. Once, my son woke at night and saw the light on. The next day, I’d be off on a trip, sleeping on newspapers spread on the floor.”

Many say snowscapes risk monotony. Unlike blue-green landscapes depicting all seasons, snowscapes capture only winter and early spring. The core challenge is using brushwork to convey snow’s depth, texture, and chill. The monochrome palette must also differentiate still snow, drifts, and blizzards.

Porcelain adds another layer of difficulty. He Xuren solved this by adapting his classical Chinese painting training (rooted in Song and Yuan dynasty studies) to create “snowscape ink painting”—using ink for outlines and overglaze colors like famille rose and glass white for fills.

During this period, Yuan Shiwen refined his craft further, merging the Wang School’s landscapes with snowscapes while emphasizing diverse, logical compositions.

Snow lacks color but reflects its surroundings.

▲ Father and son sketching outdoors

Yuan Shiwen often sketched outdoors, filling a blue plastic notebook with scenes. He also archived nature documentaries, music videos, and films—any footage of landscapes—building a categorized “library” in his studio.

His snowscapes gained dynamism: sunny snow tinged blue, dusk snow glowing red, stormy snow ominous. Snow-draped objects shifted visually—sharp edges softened, roads blurred, houses shrank. Skies and streams darkened; snow gleamed translucent.

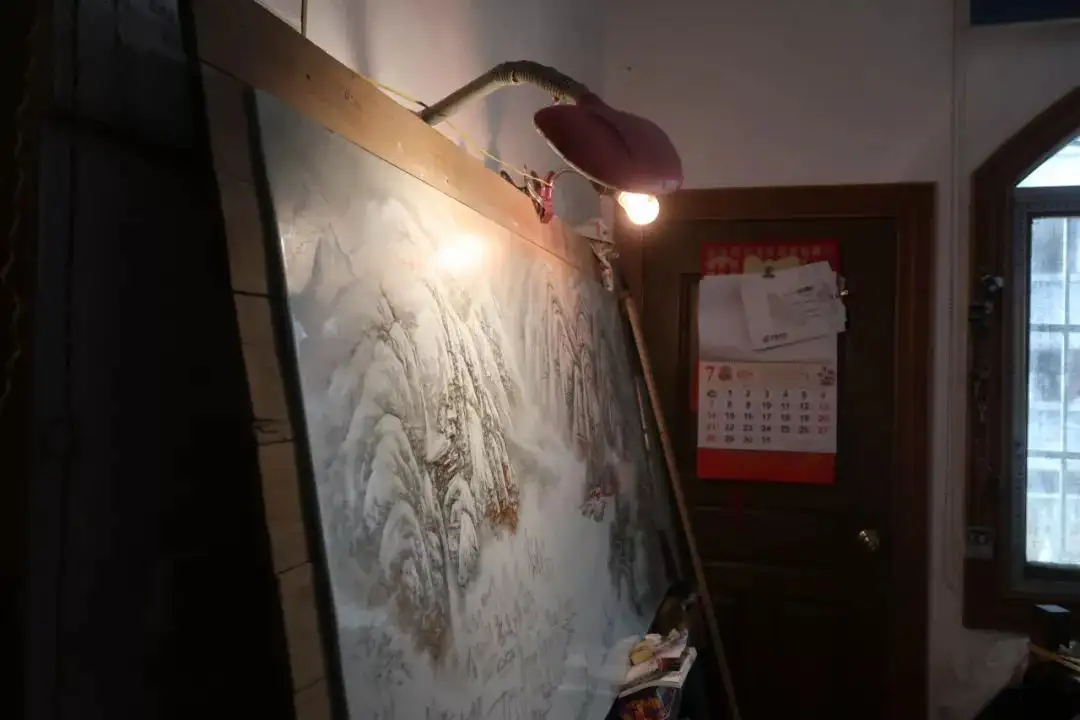

▲ Yuan Shiwen’s works

He also loved depicting small human figures in snow, a Wang School hallmark. Travelers leaning on staffs, scholars at desks, friends meeting on paths—each had distinct expressions. Farmhouses nestled in valleys; distant pagodas hinted at monks’ presence. Viewers and subjects seemed to lock gazes, the frozen landscape becoming a portal to an “ideal life.”

“I supported eight people back then: three kids, two grandmothers, two younger brothers, and my wife, who didn’t have steady work.” Like winter’s temporary blanket, hardship passed as long as resilience remained.

“My children never knew such struggles,” he says, eyes crinkling with a smile.

03 Imitation: A Double-Edged Sword

Unlike his father’s strict upbringing, Yuan Zhiyong learned in a relaxed environment.

The family wasn’t wealthy, but society was simpler. Their combined living-dining room hosted friends and colleagues for meals and chats. Neighbors were close-knit—”grabbing a bowl to share dishes here, rice there.” Yuan Zhiyong recalls those times fondly.

Surrounded by art, he often copied adults’ drawings with chalk on the floor.

Noticing this, Yuan Shiwen tossed him a copy of the Mustard Seed Garden Painting Manual.

Yuan Zhiyong thrived on his father’s “mysterious encouragement.” “Once, he bought a watermelon for the family but told me, ‘This is just for you.’ Kids thrive on praise—it gave me energy.”

With Wang Yeting’s original sketches at home and his father’s coaching, Yuan Zhiyong progressed quickly. People praised him: “Wow, this looks just like Wang Yeting’s work!”

▲ Yuan Zhiyong’s works

At first, he was flattered. “Of course it looked like his—I copied directly. As a descendant, I had access others didn’t.” But over time, he questioned it. “Even if I outdid his imitation, it wouldn’t be mine. I remember a Chaplin impersonation contest—Chaplin himself couldn’t have won.”

He sought change, but early attempts to diverge from tradition met resistance. “My early works were hyper-detailed, emphasizing labor-intensive precision. When I tried shifting styles, people disapproved. I wasn’t anxious—just unsure if I was right or wrong.”

Landscapes may seem similar, but each artist’s approach differs. For rocks, Wang Yeting used “folded ribbon” strokes with some “hemp fiber” texture; his daughter Wang Guiying preferred “axe-cut” and “hemp fiber”; later generations used “chaotic hemp.” The variations reflect the artist’s mind, not the scenery. Mere replication is mediocrity.

“My innovations might not succeed, but they’re true to me,” Yuan Zhiyong says. He also studied sketching, oil painting, and watercolors to broaden his skills.

04 That Timeless Atmosphere

Still Missed Today

▲ Yuan Shiwen tending his vegetable garden

The two now live in an old neighborhood. Jingdezhen summers are scorching; by late afternoon, the asphalt radiates heat. Yuan Shiwen often strolls from home, hands clasped behind his back, crossing the street to a small supermarket and adjacent tea shop where neighbors and acquaintances gather.

He cherishes these chats with old friends—teachers, business owners, ordinary folks—all mingling across social lines. It reminds him of younger days when no one locked their doors at night.

“Now, houses are bigger, cars everywhere. To meet someone, you have to travel far.”

This nostalgia echoes both father and son’s shared sentiment—like golden sand settled at the bottom of time’s river, offering enduring nourishment.

Yuan Shiwen often visits his son’s second-floor studio. Sometimes they disagree. “He pulls rank as a father,” Yuan Zhiyong jokes, calling family to vent—though he usually concedes his father’s points.

“His work’s still ‘green,'” Yuan Shiwen concludes.

Yuan Zhiyong protests, “Say ‘young’ instead.”

Yuan Shiwen bursts into laughter. He doesn’t feel old either. He rises at 6:30 a.m., exercises with a soft ball or treadmill, tends his garden for an hour or two, and paints for three more. His focus remains razor-sharp. “When I paint, I’m meticulous. Once immersed, I break through creative blocks fast.”

His third-floor studio houses a massive easel for three-meter porcelain panels, bearing his sketched outlines. Sponges, scrapers, and other tools sit nearby. His “library” fills white plastic bins with books and CDs—from 60s-70s films to modern health exercises—his virtual trove of landscapes.

▲ Yuan Shiwen’s collections

A Sony tape deck and full stereo system—his splurge from years ago—pumps out disco beats. Multicolored lights swirl across the ceiling like a kaleidoscope, the pulsating rhythms unleashing raw, joyful energy.

“I listen to this while painting. It’s invigorating!” he shouts over the music.

The dance tracks play on. So does youth.

Wu Yixun: The Romantic Creator

- 22 Apr, 2025

- Posted by Admin

- 0 Comment(s)

In the world of Jingdezhen porcelain, legends of “Master Wu” have long circulated. Before coming to Jingdezhen, he was a businessman in Guangzhou, dabbling in real estate, finance, and the internet as the CEO of a listed company.

But upon arriving in Jingdezhen, he chose the life he truly desired. He distanced himself from the crowds, retreating to a secluded village where he built his own utopia, pouring his romanticism and intellect into the art of creation.

For him, objects are his beautiful connection to the world.

Late at night, as city lights dim and people drift into sleep, the world grows quiet. But Wu Yixun is wide awake—this is his favorite time of day.

Settling into his study, he selects a favorite pipe, fills it with tobacco, and loses himself in thought. Only at this hour is he completely immersed, free from distractions. Massive bookshelves line his study and dining room, their covers worn and yellowed with age. From Western philosophy to experimental psychology, classic literature, art history, and countless folios, these books form another realm of his spirit—a place where he draws nourishment.

Perhaps the only things that can defy time are sincerity and romanticism.

01 The Gene of Romanticism

Born in the 1960s, Wu Yixun grew up in a prominent Guangzhou family that emphasized liberal arts education. His parents, well-educated themselves, prioritized aesthetics for their children—a rarity in those less affluent times. Alongside his siblings, he was steeped in the classical arts of poetry, calligraphy, painting, and music.

At five or six, he was a willful child, but his father encouraged him, leading him to study calligraphy and painting. A vague sense of beauty began to take root.

He was precocious in matters of the heart, a deeply emotional person. By middle school, he had a childhood sweetheart. Later, despite excelling in science, he chose to study Chinese literature at Sun Yat-sen University—simply because he found it romantic. He loved poetry, literature, and all forms of romantic expression.

His university days were filled with debates over literature, soccer matches, sculpture, and philosophy books. It was an era of idealism, where everyone dreamed of contributing to the nation. His childhood ambition? To become a writer or literary scholar.

After graduation, he worked as a journalist in Shenzhen and Hong Kong, penning investigative reports and occasionally rubbing shoulders with top artists and scholars. But curiosity about the world soon pulled him away. In 1988, he enrolled in an Australian university to study art history—no small feat in an era when international travel was far less common.

Later, as reported, he ventured into business, achieving financial success but also a growing disillusionment. Wealth accumulated, yet it felt hollow—none of it was romantic enough.

So, true to his restless nature, at the age of 40, he left it all behind. In 2009, he retreated to Jingdezhen to make porcelain.

The day we met him, he was in a quiet village in Fuliang. Even a taxi driver with a decade of experience in Jingdezhen had never been there. Navigation failed us, leaving us to rely on landmarks like roadside trash bins.

Now, he lives contentedly in his three-story home.

Dressed in a white shirt and black-framed glasses, his hair graying, he seems worlds away from his past identities: top student in Chinese literature and art history, journalist for China News Service, CEO of multiple listed companies. Yet, time has left little mark on him. The curiosity for Eastern aesthetics, the thirst for novelty, the unwavering self-belief of his youth—all remain.

02 Objects as Another World

His home is a bright, airy space. The high-ceilinged living room on the first floor elegantly displays his collections and the works of Xun Tang. But these pieces are merely the tip of the iceberg.

His lifelong obsession with beauty has fueled a deep interest in traditional Chinese culture. Over the years, he’s spent lavishly on collections—landscape paintings, Ming-style furniture, jade, Taihu rocks, Ru porcelain, rare teas, Buddhist statues, wood carvings—all acquired on a whim, authenticity be damned.

Eventually, his treasures overflowed his home. Over a decade ago, he co-founded a gallery, which also filled up. So he bought a valley at the foot of Lianhua Mountain in Sanbao Village, building his dream space: the Zhenru Tang Ceramic Museum.

To him, no material rivals porcelain’s allure. Unlike jade, which is static, porcelain is a collaboration between human spirit and nature—a drama of unpredictability.

This “language” mirrors calligraphy, literature, and painting—some explicit, some requiring interpretation, others revealing themselves through daily use.

Traditional Chinese craftsmanship holds that “objects carry the Dao.” A simple tea vessel’s lines, colors, and textures reflect contemporary lifestyles. Song Dynasty tea wares, for instance, exude tranquility, mirroring the lives of Song literati.

They cherished tea—just water, leaves, and exquisite porcelain. That was their taste. Wu Yixun doesn’t chase power or wealth; he knows his purpose.

The “Five Great Kilns”—Ru, Guan, Ge, Jun, and Ding—all favored monochrome glazes, mostly celadon, with minimal ornamentation. This epitomized the Song aesthetic: restraint, warmth, serenity, and subtlety, where form and glaze conveyed philosophical beauty, elevating spirit over matter.

Expressing beauty and life’s essence through objects fascinates Wu. Simple in concept, yet profoundly challenging. Immersed in this pursuit, a decade has slipped by.

In 2007, he founded Zhenru Tang, creating Buddhist ritual items, scholar’s objects, incense burners, tea wares, and decorative pieces using techniques like blue-and-white, famille rose, overglaze enamels, and gold tracery.

He designs these works during his nocturnal creative bursts. Those who know him understand—he’s a creature of the night, requiring solitude to think and create.

Though untrained in ceramics, his artistic sensibility and cultural grounding, coupled with his “outsider” status, freed him from Jingdezhen’s then-prevalent imitation trends. He followed his own vision.

Many of his students now populate Jingdezhen’s ceramic scene. Half the shops on Pottery Street know of Wu Yixun, and many have worked in his studio.

One industry insider remarked, “His arrival turned a new page for Jingdezhen, directly or indirectly inspiring a wave of design and innovation.” Professor Li Leiying of Jingdezhen Ceramic University noted, “He’s the most culturally thorough entrepreneur in business.”

In 2016, he distilled his name to a single character, establishing Xun Tang and moving from bustling Sanbao to a quieter village.

03 Bridging Art and Life Through Objects

Early in his ceramic career, he employed bold, exaggerated forms. Gradually, his work grew simpler and purer. He realized: simplicity is the hardest to achieve. Over-decoration distracts; stripping it away magnifies an object’s lines and essence, subjecting it to the harshest scrutiny.

A sensitive man, he obsesses over every detail.

“Lines,” he says, “can detach from concrete subjects, becoming pure spiritual expression—visual language with the rhythm and musicality of poetry.”

Compared to earlier works, Xun Tang’s current pieces inhabit a purified world: clean lines, mostly monochrome glazes, evoking the Song Dynasty. Yet closer inspection reveals subtle adjustments in form, color, and proportion, fine-tuned to feel just right.

For instance, his “Secret Color” porcelain was inspired by fragments from Shanglin Lake, brought by a friend from Cixi. Yet he deliberately distanced his creations from the antiques. Matching the ancient hues precisely would’ve been easy, but his goal wasn’t replication—it was self-expression.